The results are clear. AP&T’s Multi-Layer Furnace is very well suited for press hardening sheet metal with strength in the range of 1800 to 2000 MPa as seen by tests that AP&T recently conducted with ArcelorMittal to investigate the risks of hydrogen embrittlement.

By using ultra-high-strength steels with reduced thickness for press-hardened components, vehicle manufacturers can continue to reduce the weight of cars – and thus energy consumption – while maintaining, or even increasing safety.

But steel with a tensile strength of up to 2000 MPa also makes greater demands on process control and monitoring to reduce the risk of what is known as hydrogen embrittlement. This phenomenon occurs when hydrogen from the surrounding air migrates into the sheet metal during heating, making it more brittle and susceptible to cracking. Hydrogen embrittlement is particularly concerning in the automotive industry, especially in hot and humid countries where press-hardened steel components are produced. To keep this risk under control, it is important to regulate the dew point of the furnace air, that is, the temperature at which the air becomes saturated with moisture and water vapor begins to condense into liquid water.

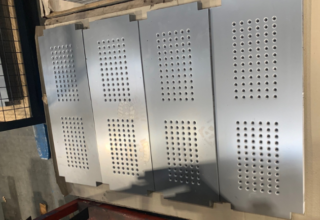

How sensitive is the process? Together with steel manufacturer ArcelorMittal, AP&T recently tested press-hardening components produced with the ultra-high-strength Al-Si-coated material – Usibor® 2000 AS – in a Multi-Layer Furnace in a humid environment. The aim was to see whether the furnace’s dew point regulation, by dry air injection, is efficient enough for avoiding hydrogen embrittlement, even under worst-case conditions.

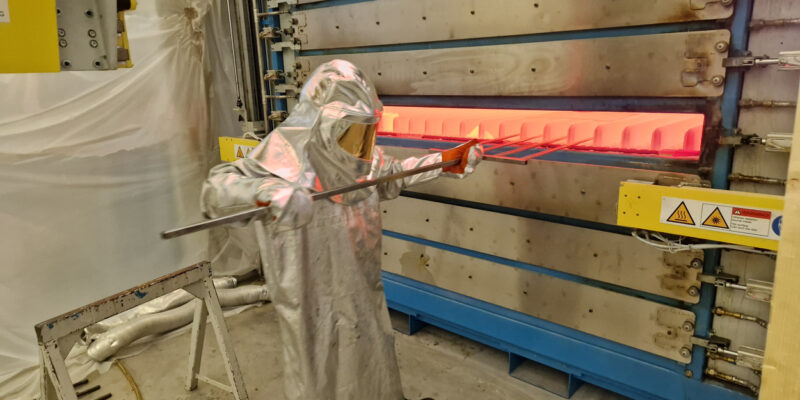

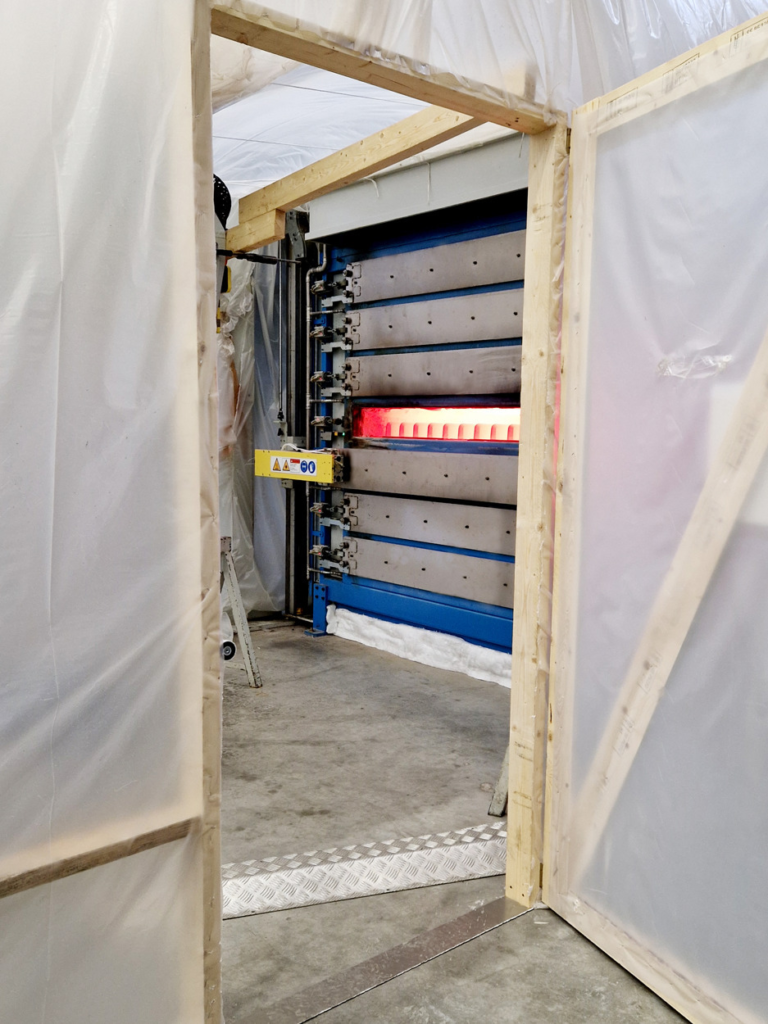

At AP&T’s development department in Ulricehamn, Sweden, a climate chamber was built around the furnace used in the testing. It had a relative humidity of 70 percent and a temperature of 30 degrees C.

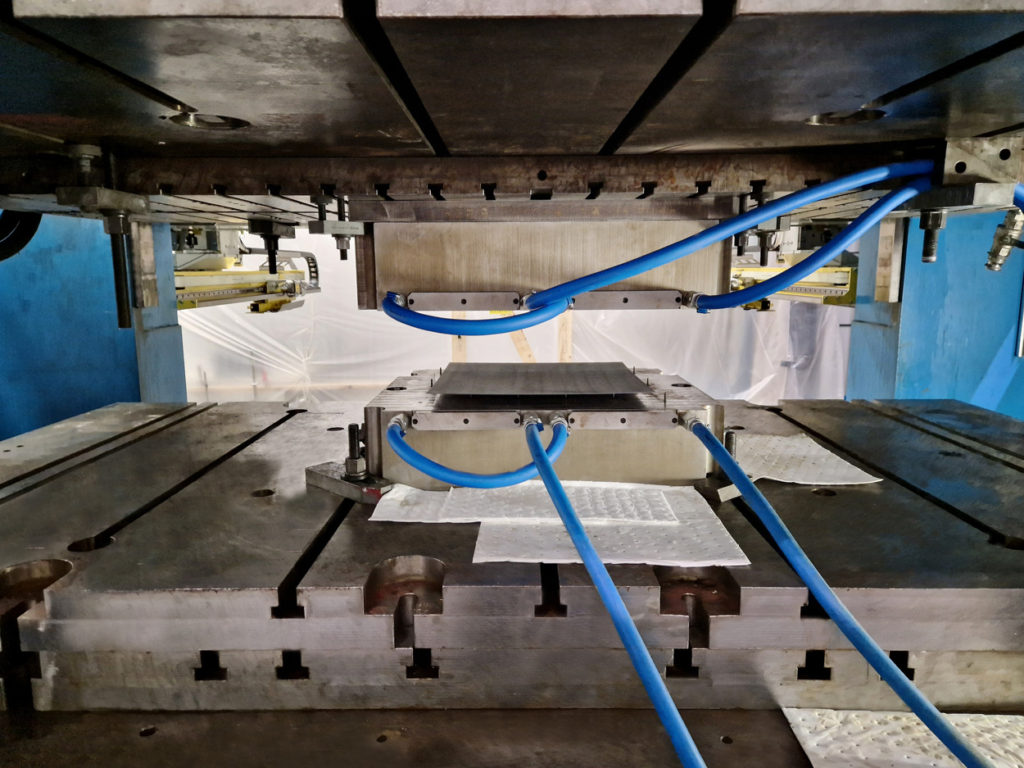

When the furnace door is opened and the material is placed inside, air enters from the surroundings. To reduce the humidity and thus regulate the dew point, dry air is injected into the chamber. A number of tests were carried out, supplying both large and small amounts of dry air under rising furnace temperatures. When the sheet metal blanks are removed from the furnace, they have a temperature around 900 degrees. In the next step, they are pressed and quenched down to around 80 degrees in a tool.

Within two days of completing the tests, the samples were stored in dry ice and transported to France for analysis at ArcelorMittal. And the outcome?

Results showed that the hydrogen content in Usibor® 2000 AS remained low, around 0.1 ppm, regardless of whether large or small amounts of dry air were injected in the process. Conclusion: AP&T’s Multi-Layer Furnaces’ dew point regulation system with dry air injection is efficient to minimize the hydrogen intake with aluminized press-hardening steels and thus very well suited for the safe production of parts with aluminized press-hardening steels with strengths of up to 2000 MPa.